Mar 03, 2015 Carsick and Role Models by John Waters

When a friend recently asked me what I’ve been reading, my response was “just some trash.” And I meant it. Lately I’ve been catching up with the works of John Waters.

One of the Baltimore-based writer’s books is actually called Trash Trio and others have subtitles referring to obsessions and bad taste. Of course, Waters is also the underground filmmaker and champion of filth best-known for Hairspray, which was not only a crossover hit but became a Broadway smash that became an actual big-budget Hollywood movie. Triply subversive! His early, lowbrow, indie films (Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, Desperate Living) altered the way I viewed cinema and widened my approach to culture in general. But his books were perhaps even more influential to me as a person who writes for a living.

I loved how the essays in Shock Value and Crackpot were funny and entertaining and disruptive as hell but with bulletproof grammar and excellent style. And the way Waters conveys unbridled enthusiasm (or spite) and scatters references that go right over most people’s heads (but demand research by true fans) not only reinvented the idea of pleasure reading for me when I was an English major in college but influenced the work I did with Giant Robot years later. Why shouldn’t a writer have at least as much fun as the audience?

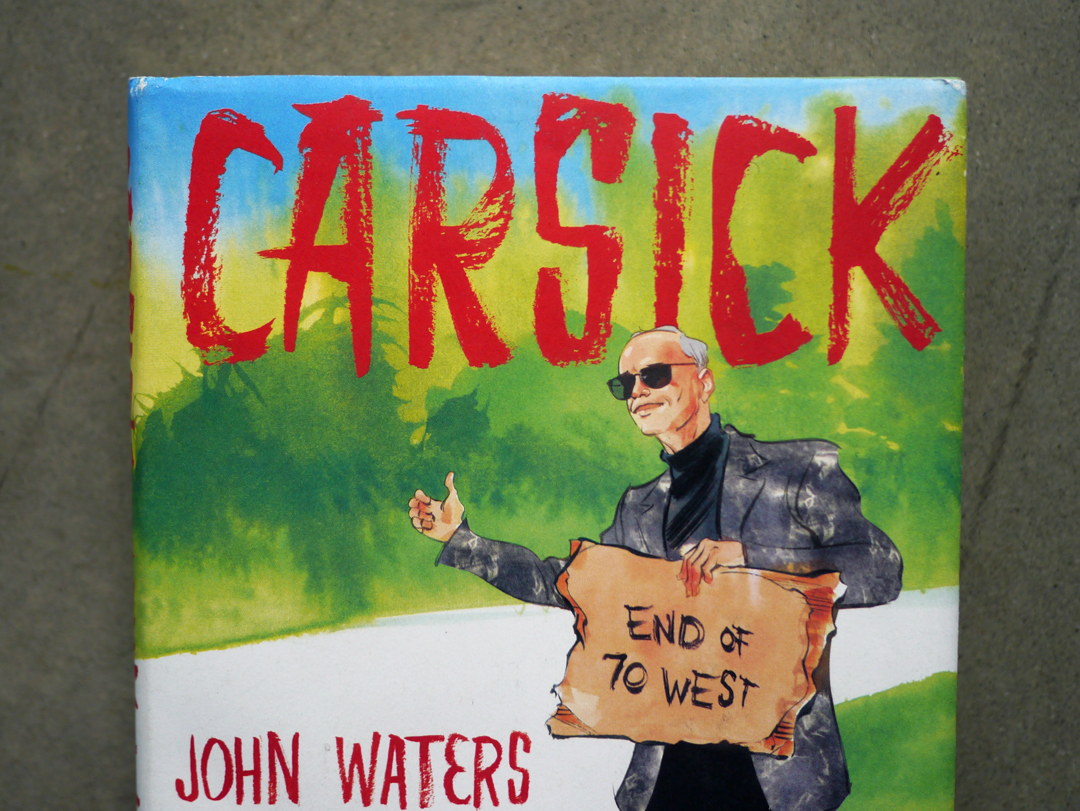

Last summer’s offering by Waters, Carsick, is centered around the 66-year-old filmmaker’s harebrained scheme to hitchhike across America. Somehow, he got his publisher to sign off on the questionable idea and I remember news circulating when a band called Here We Go Magic gave him a lift in their tour van. Then I promptly forgot about the book until Waters did a series of sold-out talks to promote it. (At least I saw him give a reading of Crackpot and even attended a screening of Polyester in Odorama at UCLA.)

The recounting of the journey is a real page-turner, but it can only disappoint after the first two sections of the book: best-case and worst-case novellas. The idealized trip features characters such as a mysterious demolition derby driver who invites Waters to ride shotgun and redefines the term autoerotic, a porn parody book connoisseur/banned book vigilante, and Edie Massey the Egg Lady (fans will know her, and perhaps even cry). The doomed version includes a run-in with true crime trivia answer Gertie Baniszewski, introduces the term “junkie hag,” and describes a special place in hell dedicated to non-mainstream filmmakers. Wow.

The two novellas are not only fever dreams but crucial reading–up there with his “How Not To Make Movies” (should be mandatory for every filmmaker) and “Why I Love Christmas” (which I will read to my daughter every December, eventually) essays. The factual section is perhaps even more bold than the fiction because it actually happened, but it is also limited by the boundaries of reality and tainted by the use of modern technology for safety purposes.

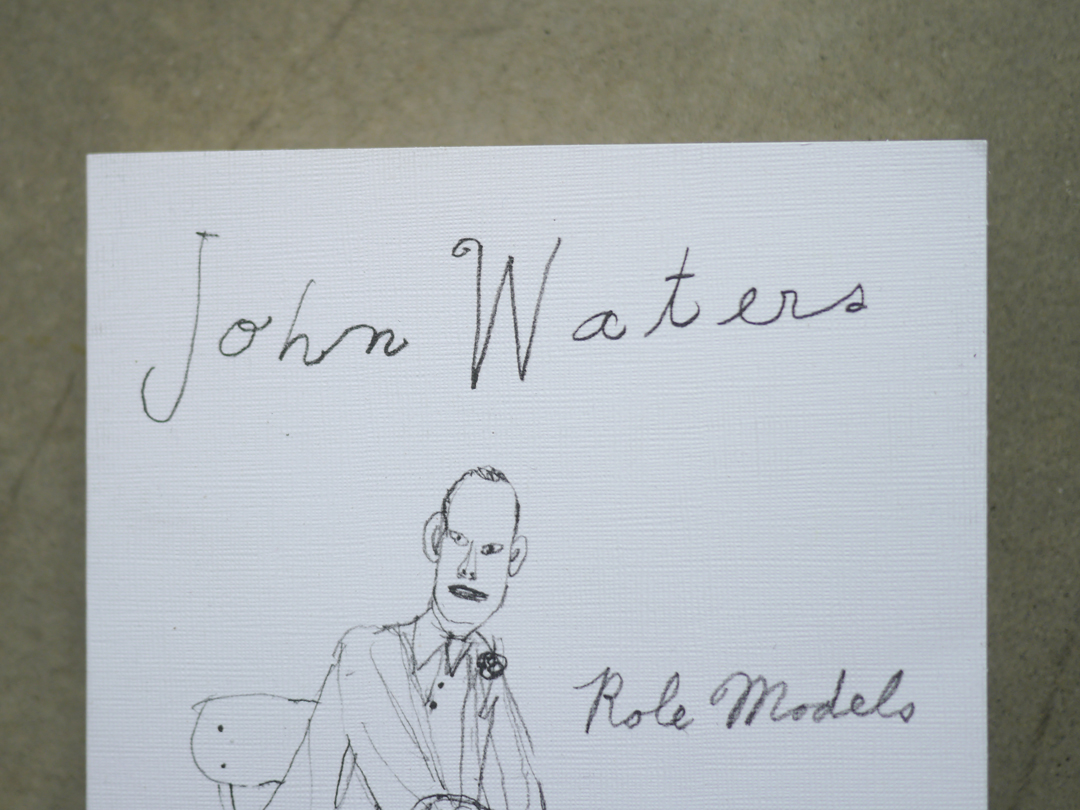

The nonfiction segment of Carsick sorta celebrates the everyday people of America, from Baltimore to San Francisco, and so does his previous book. In 2010’s Role Models, Waters writes profiles about people who’ve had an effect on him from hometown strippers and bar owners to Johnny Mathis.

Some of the pieces are actually highbrow. His gushing over Rei Kawakubo goes beyond fanning out into idol worship. Incredibly, his chance to meet the infamous designer of the elite clothing brand Comme Des Carçons and model her clothes actually heightens his feelings rather than disillusion or disappoint. The essay about one of his literary heroes and gay figurehead Tennessee Williams intelligently and respectfully emphasizes the playwright’s “bad” side. And when Waters is granted an audience with the middle-of-the-road crooner of “Wild Is the Wind,” his intense and genuine admiration is nearly impossible to believe. In fact, Mathis seems to be the entire reason for writing this book!

Other essays harken back to the author’s Shock Value days–and then some. There’s no hyperbole or embellishment necessary for the tribute to outsider pornographers just like there’s no need to push Little Richard’s buttons when interviewing him for Playboy. They’re already so out there that Waters simply asks them questions and gets out of the way. But his genuine love for the subject matter comes through, and so is the lack of irony. Waters isn’t a poseur who makes fun of people or follows trends. John Waters is a true original–and so are his movies and books.

There are not many book reviews but a lot of interviews, articles, and events posted by Imprint via Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.